Liam Wynn

This is my site. Here, I make neato projects and blog posts.

Texture Generation Using Variational Autoencoders

Hello all! In this post, I want to describe a fun experiment in machine learning I did some months ago. This was using a variational autoencoder to create textures. In this article, I will document the problem I had, the model I used, and then the results.

What are textures?

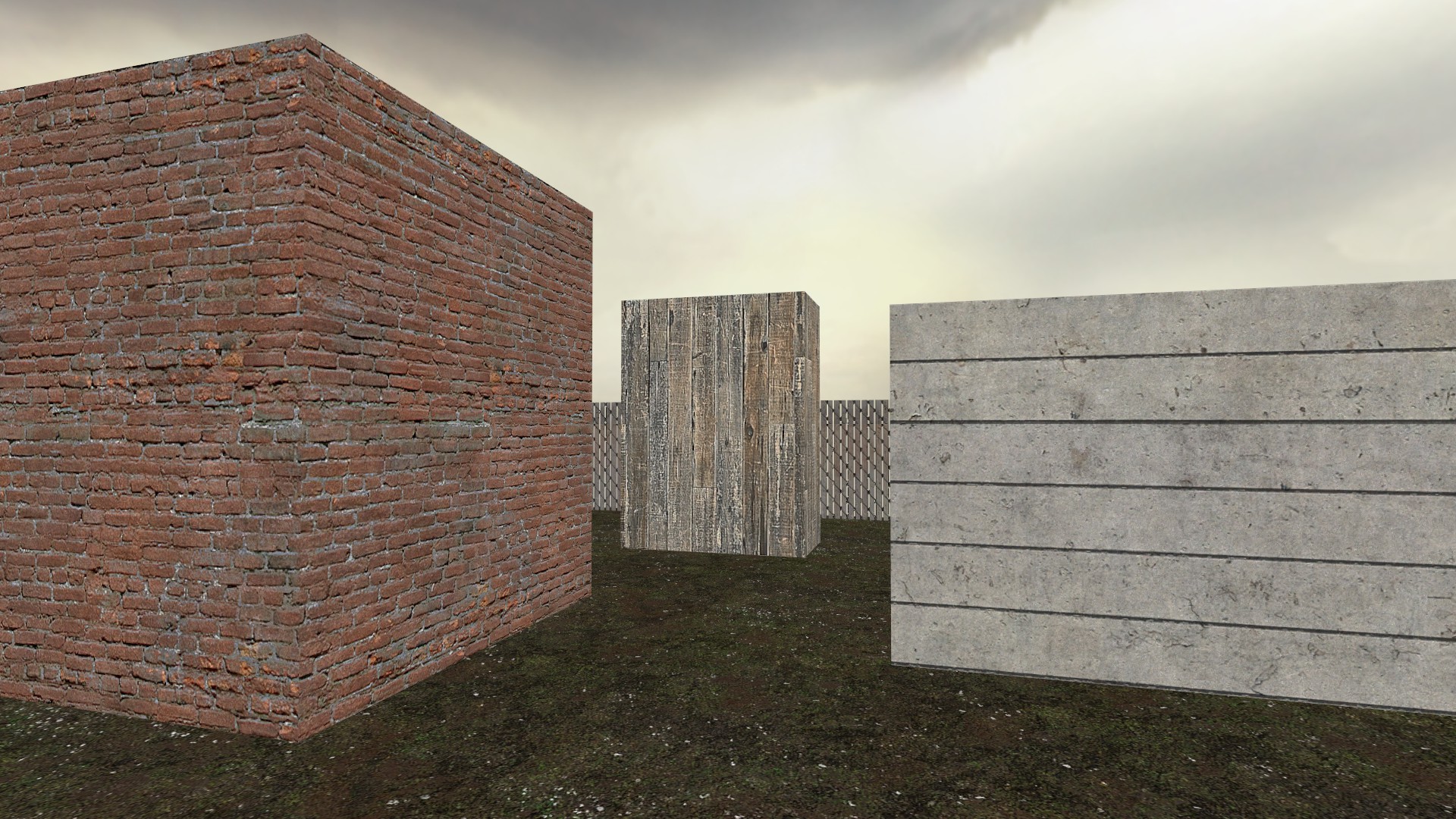

To begin with, let’s define what a “texture” is. The definition of “texture” is kind of hazy. In games, a texture is a qualitative description of something’s surface. Take for example this picture I took from a simple level I made for Half Life 2.

You can see the ground, a fence, and three blocks. We can describe the respective texture of each of these as follows:

- The ground has a damp, dark green, grass texture

- The background has a metalic fence texture

- The three blocks (from left to right) have brick, wooden plank, and concrete textures

For these, the texture is represented by an image. I will briefly note that textures needn’t be images strictly. The sky has a texture that isn’t an image unto itself. Depending on the engine used, such textures may be elaborate pieces of code, or (in the case of Half Life 2’s Source Engine) the use of six images that form a “skybox”.

In the case of my model, I wanted to generate texture images with a special property: being “locally similar”. Take the brick texture of the leftmost block in the image above. Now look at different areas of this block. You’ll notice that the texture (red brick) is similar no matter where you look. In other words, a texture of the kind I want has repeating or similar patterns/shapes no matter what portion of it you’re looking at.

The problem (and how machine learning can solve it)

Okay with this background, we can now get an idea of what our problem is. As the name of the project implies, I wanted to be able to generate these texture images. The grand vision would be that I could specify the kind of texture I want and the system would spit out some kind of generated sample.

For example, I want a “honeycomb” texture, and perhaps it gives me one of the following:

(These are examples of what my model ended up actually generating)

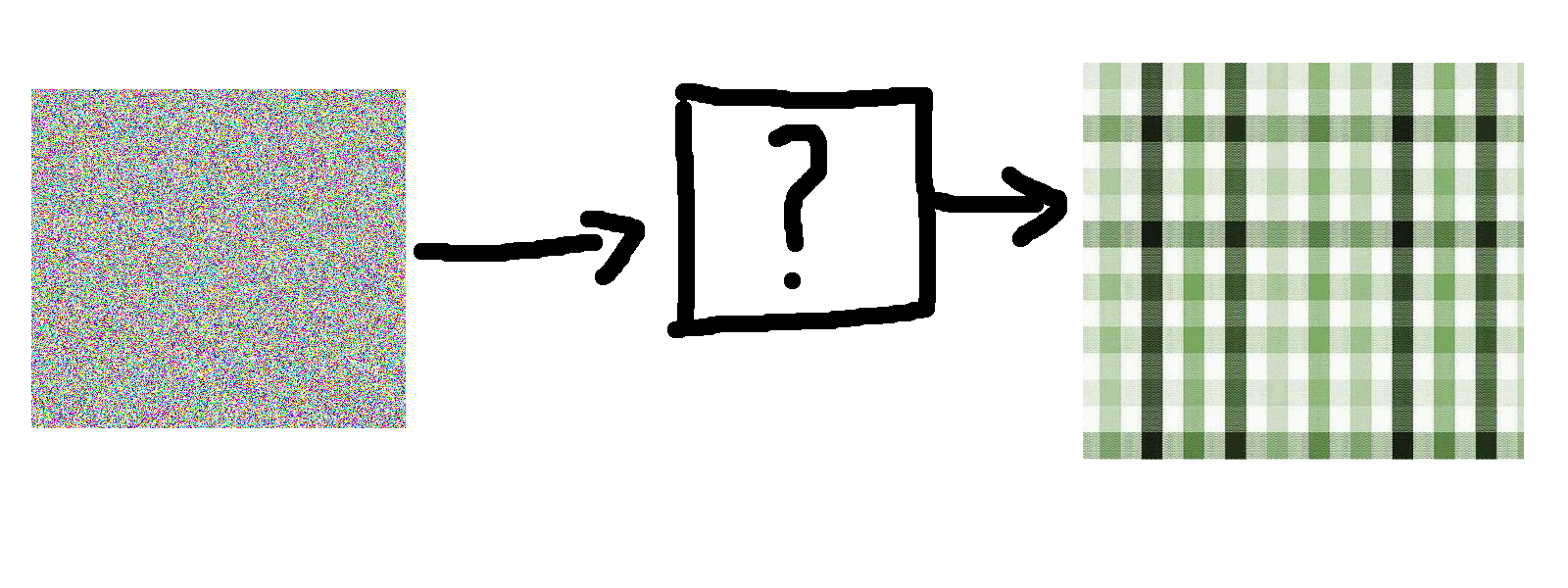

Broadly speaking, how would this be done? We will basically need to take as input some noise, and spit out a texture. Visually, our problem is as follows:

Now, as far as I can tell, there isn’t an obvious function or algorithm that maps say noise to generated texture samples. That’s where machine learning comes in: it helps us find mappings between domains that aren’t otherwise apparent. So let’s take a quick survey of models that I found weren’t suitable, and then we’ll get into the varational autoencoder.

Models and techniques that I found insufficient

Texture generation (also called “texture synthesis”) is not a new problem. Here are some of the algorithms I thought about using or exploring and why I didn’t use them

Image Quilting

Essentially, you take a source texture image, and randomly sample from it. These samples you “quilt” together onto a larger surface. This graphic from Douglas Lanman explains it:

What I like about this algorithm is that it’s simple: you don’t need an elaborate model to get good results. However, the problem is that it takes as input a sample texture and basically shuffles that. What I want is to generate entirely new samples without relying off of given samples at generation time. You see, I will use samples to learn a mapping between noise and textures. Once I have that mapping, I should no longer need samples to generate textures.

Gatys et. al. Method

In what was a follow up to their famous Style Transfer, Gatys et. al. employed the same style transfer technique, but applied to noise. So given a source texture, and a noise image, they produces a new texture image. The paper for this is here

As great as this method is, it has the same problem as quilting: at generation time, I have to give the system a sample texture to work with.

Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks

The current state of the art for such a generative approach is the GAN (Generative Adversarial Networks). Since I’m doing something with images, I want a DCGAN. Essentially, you have two competing networks. One that is training to identify real examples of the space you want to model from fake ones. The other network is trying to generate phony examples that look like real ones. These two networks are essentially playing against each other. In theory, as they play against each other, they both get better at their respective tasks.

If you’re interested, Alec Radford and Luke Metz published a seminal paper showing the power of DCGANs.

I had used this model for my final in CS 446: Advance Topics in Machine Learning (as taught by Anthony Rhodes) in the Fall of 2018.

While this model worked, I found it had some annoying issues. First, as long as the generater network (the one producing phony examples) could fool the discriminator network (the one seperating phonys from real ones), it was “good”. This means that for a long period of time, the generator can feed the discriminator noise and still fool it. It’s only after awhile that the discriminator can properly identify what it’s looking for.

Second, I found the DCGAN was prone to collapse. I think this is what they call modal collapse. Essentially, the training just falls apart and the discriminator fails entirely to learn the space of real samples. The generator can give it some junk “example” and no matter what it passes.

Variational Autoencoders

Now that we’ve seen some models that I didn’t like, let’s explore the one I did like: the Variational Autoencoder. Whereas a GAN has two networks that compete, a VAE has two networks that cooperate. The two networks are called the encoder and decoder networks. Essentially, the encoder will take an input image and “encode” it but mapping it to a latent space. Then, the decoder will do the reverse process: take the latent values and reconstruct the input.

VAE’s have several uses. An obvious example is data compression. Suppose I find an image on the net I want, so I save it. If the image is high res, then I will be transferring a lot of data. So instead, we encode the image into a vector from some latent space, transfer said vector to my device, then decode it to my original image.

In my case, I train a VAE to learn to encode texture images into a latent space, then take the latent space values and decode them back into the input image. Once my VAE is sufficiently trained, I use my decoder network as the generator. I can basically plug in random values for my latent space, and then have the network decode these values into a generated texture.

A brief explanation of how VAEs work

There is a wealth of tutorials that dive into the innards of the Variational Autoencoder. The two most useful ones I found are here and here.

Nonetheless, I will do my best to at least give an overview of how VAEs work. The encoder network is your typical neural network. Your input is a vector of values that go through a series of network layers until it reaches the output. The output is two vectors: one of means and one of standard deviations. I call this the “latent space” because we don’t really know how the values relate to the input. That is, we don’t know how tuning these values will affect the output, hence it is hidden or “latent”.

The decoder network works by using these means and standard deviations to sample from a normal distribution. If you were wondering how we know what values to use for the input of the generation step above, this is how. The means and standard deviations are used to get a vector of normally distributed noise. This noise is what is fed into our decoder, not the means and standard deviations.

The loss of the model is the sum of two values: the reconstruction loss and the latent loss. The reconstruction loss is the squared difference between the input image and its reconstruction. The latent loss is the KL Divergence between a normal distrubtion and the gaussian distribution formed by our latent means and standard deviations. The goal is to make this as close to a normal distribution as possible.

Overview of the Model

Okay so now I will give a specification of the model I used. There will be three parts: the encoder network, the decoder network, and the optimizer algorithm I used.

The encoder network is as follows:

- It has three convolutional layers with drop out applied.

- Each of the convolutional layers has leaky ReLU activation applied to it

- Then it has two seperate dense layers that compute the give us the mean and standard deviation vectors. Both of these vectors have eight values in them.

The decoder is as follows:

- It has four transposed convolutional layers, each with drop out applied.

- The activation for the first layer is ReLU, while the second two have leaky ReLU applied. The last one has sigmoid activation.

Finally, the optimization algorithm used is the Adam Optimizer with a learning rate of 0.0005 applied.

Results

I trained the model for 3001 epochs. Having it run on the GPU made training a cinch, because it took only about 30 minutes or so. As you will see, the results were very stellar. I hadn’t expected a somewhat antiquated model (in “tech time”, 4 or 5 years is dated) to do so well.

In fact, I had initially gone with a GAN because it is state of the art. However, a powerful model needs a lot of data to work with, and it has a lot of ways it can fail, as I explained above. So using the VAE for this proved to be a wonderful suprise.

I shared these textures before, but I will share them here again:

Future Work

Not all of the generated examples were perfect, of course. A few came out very blurry. I think this can be rectified in two ways:

- Use more training data. I gave the model only about 6 or so source images to learn from, so having more could learn a richer space.

- Let the model run longer. This way it can learn the texture space and thus avoid blurry results.

And if you’re wondering why there’s only these honeycomb textures, it’s because I only trained on honeycomb textures. I would like to create models for more texture types. Furthermore, the textures themselves are greyscale. This actually doesn’t bother me too much because I want to learn the texture features themselves independent of color.

That said, I want to add color to my resulting textures. I hope to have a program in the future that would take an input like “three red honeycombs” and spit out three generated honeycomb textures with red coloring.

Lastly, I want my generated textures to be seamless. That is, if two adjacent walls have a generated texture, you wouldn’t see an abrupt edge that clearly indicates the texture is repeating. While for some textures this isn’t a problem, imagine a patch of grass. The grass texture shouldn’t be repeating in an obvious way.

Final Remarks

I hope you enjoyed this article! If you’re interested in this project, you can check it out here.