Liam Wynn

This is my site. Here, I make neato projects and blog posts.

Spring Break News Report

Well it’s been awhile. In fact, we are close to the two month mark! I apologize sincerely for that. I was really hampered with school. Hopefully, the next term will be a little easier on me.

With that said, there’s been some cool developments. Namely, I’ve made some cool progress on Ulysses, and another project of mine: the blazonry parser. I’ll talk about the latter in a moment, but first, let me give you the rundown on Ulysses.

The last time I made a major post about it, I gave a rundown on generating height maps based on geological phenomena. In that same vein, I’ve been working on a system for simulating precipitation.

Now, I’d love to give you a glowing rundown on how great the system is. The problem, however, is that I can’t really say. I mean, it looks like it’s working. But I can’t say for certain until I finish the complementary system: temperature.

Essentially, the game plan is this: I want biomes in my worlds, like deserts, rainforests, tundras, etc. Most real world systems classify biomes based on precipitation and temperature. I have precipitation, for the most part. I still need to produce temperature. Once I have that, I can finish off this portion of Ulysses, more or less.

So in the meantime, I can discuss some of the subsystems at play to produce precipitation. In this case, I’ll discuss the production of rivers. So, if all goes according to plan, expect a post about that tomorrow.

Okay so what is the other thing I was talking about? A blazonry parser? What does that even mean? Well let’s break that phrase “blazonry parser” down. Let’s… parse it, if you will. So blazonry, roughly speaking, is what you call those neat family crests, medieval banners, etc. Think the cool flags from Game of Thrones.

Well as it happens, these actually follow a well defined grammar. Intuitively, this makes sense: back in medieval times, it was important that you could easily identify people by their banners. Further, for the purpose of identifying them, you needed to be able to easily describe their banner without any ambiguity. For more information about this, check out this page.

Defining a Grammar

I at first tried to emulate the grammar as specified in the link. I figured I would try to implement the real world one myself. However, I decided to settle on a simpler grammer. Mine doesn’t include any fancy insignias or symbols, but still follows some of the basic ideas laid out in the real grammar. I’ll give you the grammar first, and then break it down.

Blazon -> Field | Field Ordinary

Field -> Tincture | Division

Division -> "per" Div_Type Line Tincture "and" Tincture

Line -> e | Line_Type

Ordinary -> Ordinary_Type Tincture

So according to my grammar, a Blazon is either a Field, or a Field followed by an Ordinary. We then say a field is either a Tincture, or a Division. A tincture is basically a color. A division is some way of splitting the blazon into two different colors. Now the line specifies how we do this split. Do we make the split wavy? Is it straight? There’s a ton of options, and we won’t get into them at the moment. Finally, an ordinary is a simple shape like a cross or a horizontal bar.

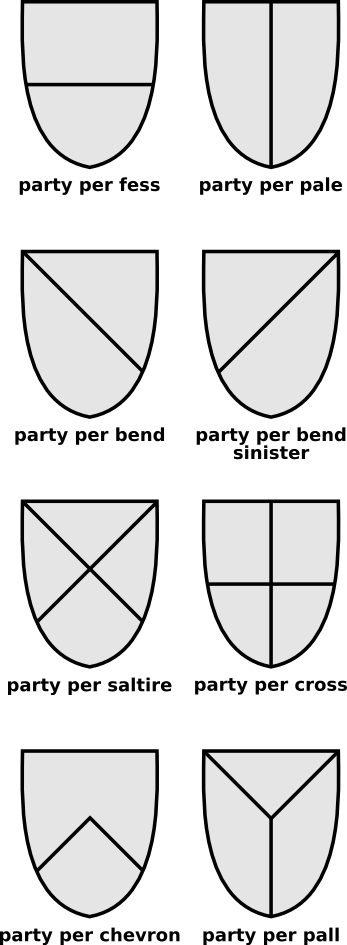

In the above picture, this gives you a visualization of the kinds of divisions your shield can have. Credit to Wikipedia

If you Google tinctures, line types, and ordinaries, you should find similar graphics that are fairly self explanatory.

Implementing the Parser

Now that we’ve a grammar, we can in theory define strings that follow this grammar. However, even after being formally taught the art of parsing in CS 311 and CS 320, I felt like it would be a daunting task. So for awhile, all I had was a grammar and a dream. That was the case until I decided, out of sheer boredom, what strings would look like that followed the grammar. Below is a simplified version of the above grammar I used.

B -> F | F O T

F -> T | D T T | D L T T

In this case, we say a Blazon (B) is described as either a Field (F) or a Field followed by an Ordinary (O) and a Tincture (T). A Field is one of three options: a single Tincture, a Division Type (D) followed by two Tinctures, or a Division Type followed by a Line Type (L) and two Tinctures. The possible strings this grammar enumerates are:

- T

- D T T

- D L T T

- T O T

- D T T O T

- D L T T O T

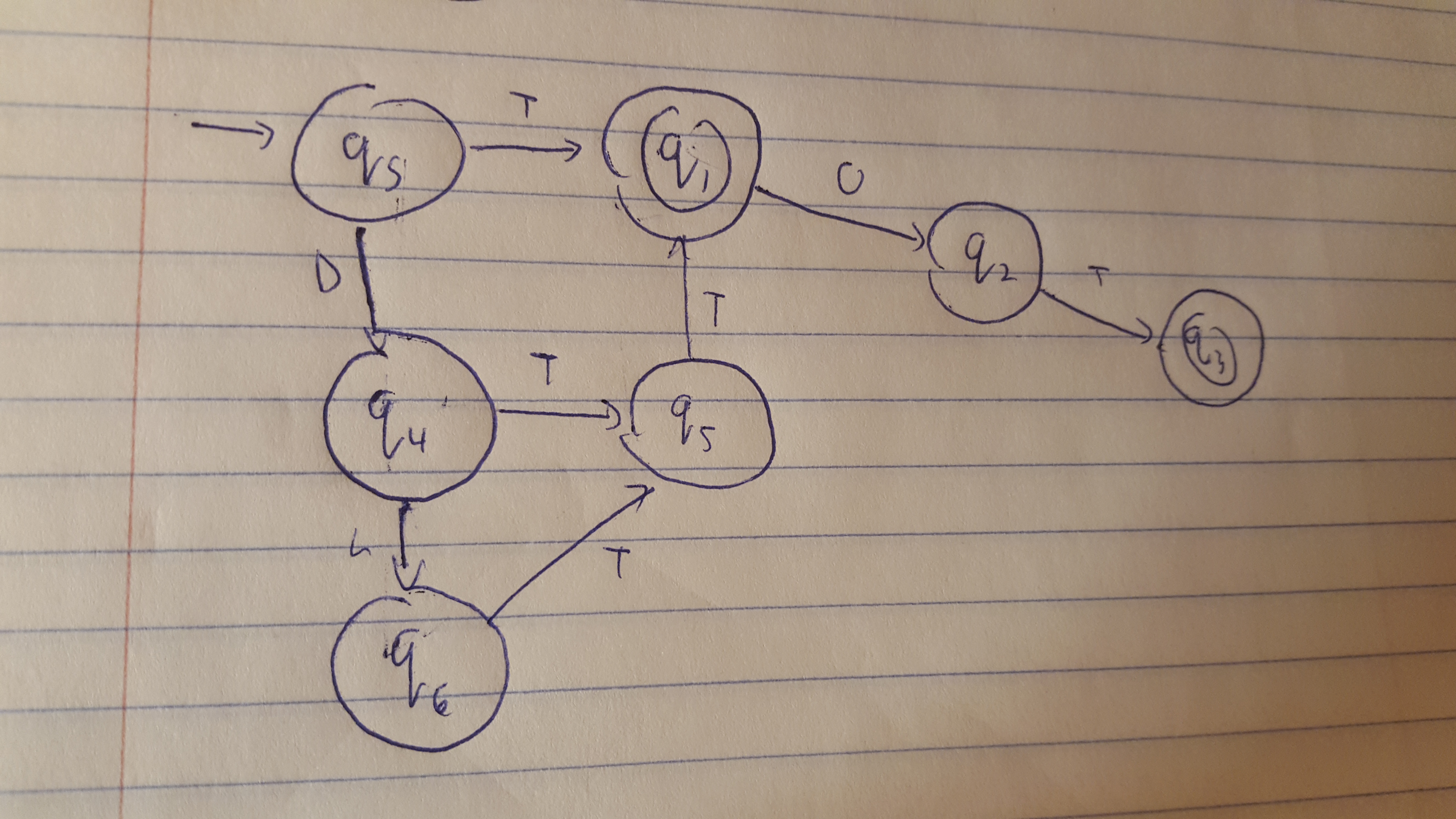

So we’ve essentially reduced the problem to determining if a string is one of these six. There are several ways you can do this. A simple if-else block would do the trick. I decided to model the problem as a deterministic finite automata, as shown here:

Using this model, I translated it right into a Haskell program.

The Implementation

First, I defined a type called Alpha to represent the values T, D, L, and O. It is defined as follows:

data Alpha = T | O | D | L | None

deriving (Eq)

instance Show Alpha where

show T = "T"

show O = "O"

show D = "D"

show L = "L"

show None = "None"

So first, we see the type Alpha can be the values T, O, D, L, or None. None is a special case for dealing with printing. Essentially, I use it to specify invalid values. Like if I want to use “Orange” as a tincture, that’s not possible. Anyways, to do comparisons with other Alpha values, I made Alpha derive from Eq.

Next, I needed to specify a type for my states. This is done as follows:

data State = Qs | Qf | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 |

Q4 | Q5 | Q6

deriving (Eq)

Note how this one derives the Eq class as well. This is important, for when we define the state transition function, which is given here:

trans :: Alpha -> State -> State

trans a s

| a == None = Qf

| s == Qs && a == T = Q1

| s == Qs && a == D = Q4

| s == Q1 && a == O = Q2

| s == Q4 && a == L = Q6

| s == Q4 && a == T = Q5

| s == Q6 && a == T = Q5

| s == Q5 && a == T = Q1

| s == Q2 && a == T = Q3

| otherwise = Qf

I decided to hard-code every possible transition. Some special cases. If no transition is specified, we go to Qf, which is the fail state. We also go to Qf if a is a type None.

Now finally, we can verify if a given set of Alphas is valid. We do so with the following function:

verify :: [Alpha] -> State -> Bool

verify [] s

| s == Q1 || s == Q3 = True

| otherwise = False

verify (x:xs) s = verify xs (trans x s)

So if the state we start in is Q1 or Q3 and we have an empty set, we return true. I decided to omit the wrapper since it’s so trivial to do. To implement it, it’d might look something like this:

verify_wrapper :: [Alpha] -> Bool

verify_wrapper s = verify s Qs

That is, we force the verify function to start with Qs. I operate on the assumption Qs is the intial state. In a real-world application, I’d make sure to do that.

Anyways, I hope you guys enjoyed this read. Be sure to check out my Blazonry Parser project for yourself on my github page!