Liam Wynn

This is my site. Here, I make neato projects and blog posts.

How I Did It: Rivers In Ulysses

So I promised a brief rundown on how I did river generation in Ulysses. Generating rivers is part of the Hydrosphere component of the overall procedural terrain generation system. The Hydrosphere is responsible for producing a precipitation map of the world.

In this post, I will first describe some of the geology behind river formation. Next, I will explain how I use this to make a simple river building algorithm. Then, I will discuss some of the additions and modifications I had to make to the system for more aesthetically pleasing and plausible rivers. Finally, I will explore ways to make this system have more depth.

The Geology of River Formation

While the science of rivers is full of depth and incredibly interesting, they only play a minor roll in the overall Ulysses terrain generation system. As such, there was really only one component of their formation that was of use to me: gravity. As it turns out, everything on planet Earth respects the laws of gravity. That is, if I hold something at a higher elevation, and I let it go, it will fall to the lowest possible elevation it can.

So what does this have to do with rivers? In sum, they begin at higher elevations, and then wind their way down to the ocean, lakes, or other rivers.

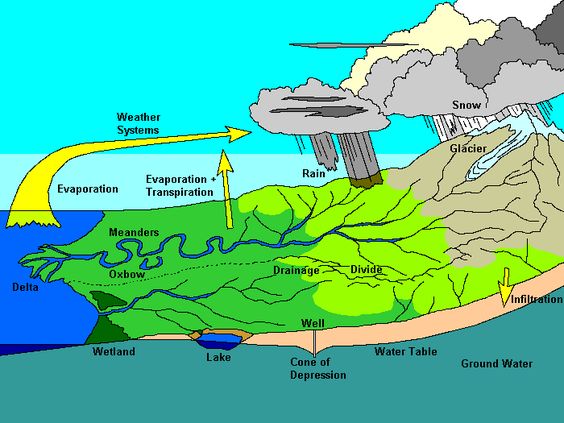

I found this one here so credit to the original author for this.

Basicaly, a river begins when precipitation collects in high altitude areas – namely mountains. This precipitation begins to spill over and work its way down to lower altitudes. As it does so, and as it collects more and more water, it eventually grows into stronger and stronger streams until it deposits into the sea or a lake. An important note here is that rivers can grow when they merge with other rivers. This plays a role in the formation of drainage basins – which is an area where multiple sources of precipitation drain into a common outlet. As we will see, drainage basins are somewhat implictily dealt with in Ulysses.

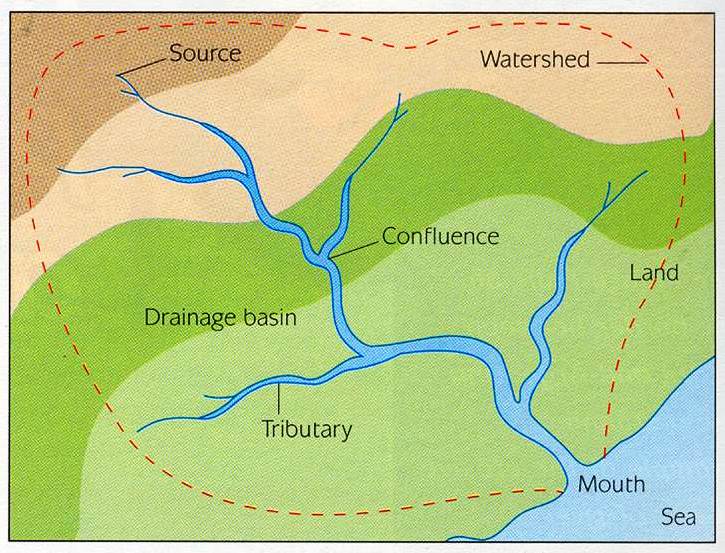

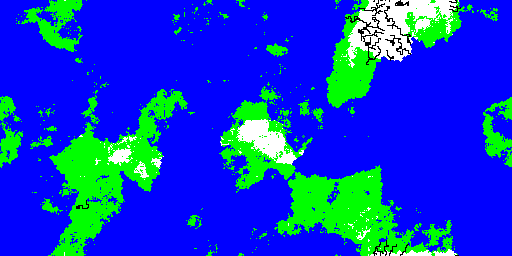

I found this picture here

For reference, here is what a drainage basin looks like.

Devising an Algorithm

So basically, to emulate the simple science above, we need two things:

- Choose the best locations for rivers to form.

- Choose a path for rivers to go.

Let’s start with the first requirement.

Selecting Where Rivers Form

As the broad overview of the science implied, rivers start in high altitude, high precipitation areas. Now, you may notice a problem here: rivers are created in Ulysses because they affect the precipitation of the world, but the precipitation of the world affects how rivers form. This is, of course, one of many examples of the pitfalls that arise from making a complicated dynamic system into a simple static system.

But all is not lost, I’m happy to say. I can represent where precipitation will fall with something I call the “Cloud Map”. Basically, it’s perlin noise that says where clouds frequently form. We once again grossly simplify the real world science.

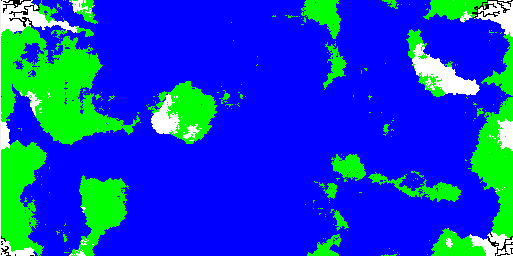

Here’s an example of what this map would look like:

Note that this is nothing more than the “not”-Perlin-Noise mystery algorithm I used in the height map generation system. Go here

Once we have our cloud frequency map, we can combine it with the height map to find the best points to start our river.

I should note that this causes some interesting yet undesirable behavior: river sources are closer together. As such, your rivers become clumped together. To fix this, I added an additional noise map that made choosing river sources more random and thus spread out.

Also, you have to make points that are oceanic 0 otherwise you could get rivers spawning in oceans!

At this point, we’ve selected our starting points for our rivers. It is time now to build them.

Building Rivers

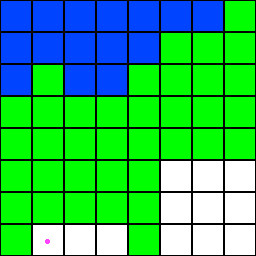

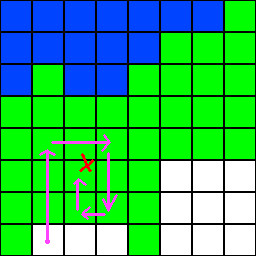

Let me begin by creating a somewhat contrived picture for you. In the picture below, let white represent mountain, green non-mountainous land, and blue ocean. We will assume that the height values each cell holds are similar between colors. That is, green cells are similar in height, white are similiar to each other in height, and blue cells are similar to each other in height.

Also note the purple dot marks the spawn point of a river.

As described above, the science of river formation is restricted by gravity. That means the river moves downward in elevation until it can drain into the ocean or another river. Naturally, our algorithm will look like this:

let p = river_source

while p is not apart of a river or not ocean:

select the lowest height valued neighbor n

set p = n

Now this seems excellent and perfect. However, here could be a result of this algorithm. The arrows show the direction the river builds:

Bummer. As it happens though, this problem cropped up in Computer Science a loooong time ago, and an excellent solution was found: depth-first search. Now, I picked that DFS because I thought it was dumb enough, as it happens. The nature of river formation is arbitrary: it wont look for the best path down; it lets gravity do the work. So our algorithm now looks like this:

p = river_source

s = stack

push p onto s

while s is not empty:

pop q off if s

if q is apart of a river or is ocean:

success!

find n = lowest height value neighbor of q

push n onto s

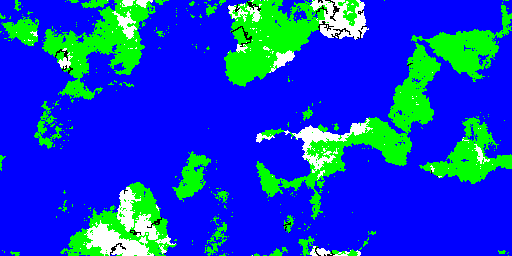

Finally, here are some example outputs with rivers. Note that for the purpose of contrast, I made the rivers black.

You may see that seperate rivers will form and drain at common points. As I had mentioned before, the system does create something akin to drainage basins on its own. You also see that rivers tend to clump near each other. I may end up choosing a different algorithm for this, as I’m still thinking about if I like that behavior or not.

In any case, we saw a rough overview of the real-world factors that influence where and how rivers form. Then I covered how I modeled the science in Ulysses itself. I’m omitting a lot of details about how we pick neighbors, how we actually implement the algorithm, etc. If you want to see how I implemented it entirely, I’d encourage you to check out the RiverBuilder class in the Ulysses source code. In any case, I hope this gives good insight into how river generation in Ulysses was done.

This will likely be the last post on features in Ulysses for awhile, as the next major part requires a fully working Hydrosphere and several other yet-to-be-complete systems. Once this is done, I will cover in full the rest of Ulysses.